Legend has it that the Umbrian Veii, a tribe living along the Tiber River, decided to build a new village on the same bank at the confluence of the Naia stream. During a meal, a cloth spread out on the ground was seized by a large eagle that swiftly descended from the sky and carried it to the top of a hill (about 400 meters) behind them. For the leader Tuder and his men, it was a divine signal for the site of the future village, or the ancient city of Tutere ('strong city,' 'high and fortified place'), later Romanized to Tuder (meaning 'border' in Latin). This was between the 8th and 7th centuries B.C., and the first furrow was traced in the area behind today’s Duomo, marking the city's walls. This district is called Nidola, or more commonly 'Eagle's Nest,' the point where the eagle had built its nest, which remains Todi’s emblem (an eagle with outstretched wings, holding a cloth in its talons).

However, it is more likely that when the Tiber waters found a way through the Forello Gorge, eliminating the swamp that once characterized the valley, the area began to attract people who built their huts higher up for defense. The natural protection of this high and steep place initially required no walls, but they became necessary between the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. With agriculture and pastoral activities, controlling transportation routes became essential for social and economic development, aided by Todi's unique geographic location—bordering Umbrian territory (left of the Tiber) and Etruscan territory (right of the Tiber). Todi was influenced by ancient Etruria, with early road connections to Orvieto, later extending to Chiusi, and a segment of wall including Via delle Mura Antiche, Via Paolo Rolli, Via del Montarone, near Porta Libera and Porta Marzia.

The most notable and representative artwork from this era, and from Etruscan art in general, is the 'Mars of Todi,' a 5th-century B.C. bronze sculpture found in June 1835 near the walls of the Montesanto Convent, now displayed in the Vatican’s Gregorian Museum.

Around 340 B.C., with the opening of key roads like the Via Flaminia (connecting Rome to Rimini) and the Via Amerina (from Veio to Chiusi, passing through Perugia) and the navigability of the Tiber, Rome began conquering the people and urbanized areas of central Italy. Rome permitted Todi to mint coins, which still bear inscriptions in the Etruscan language. Tuder saw Rome not as an invader but as an ally and even sent its contingent to the Battle of Lake Trasimene against Hannibal in 218 B.C.

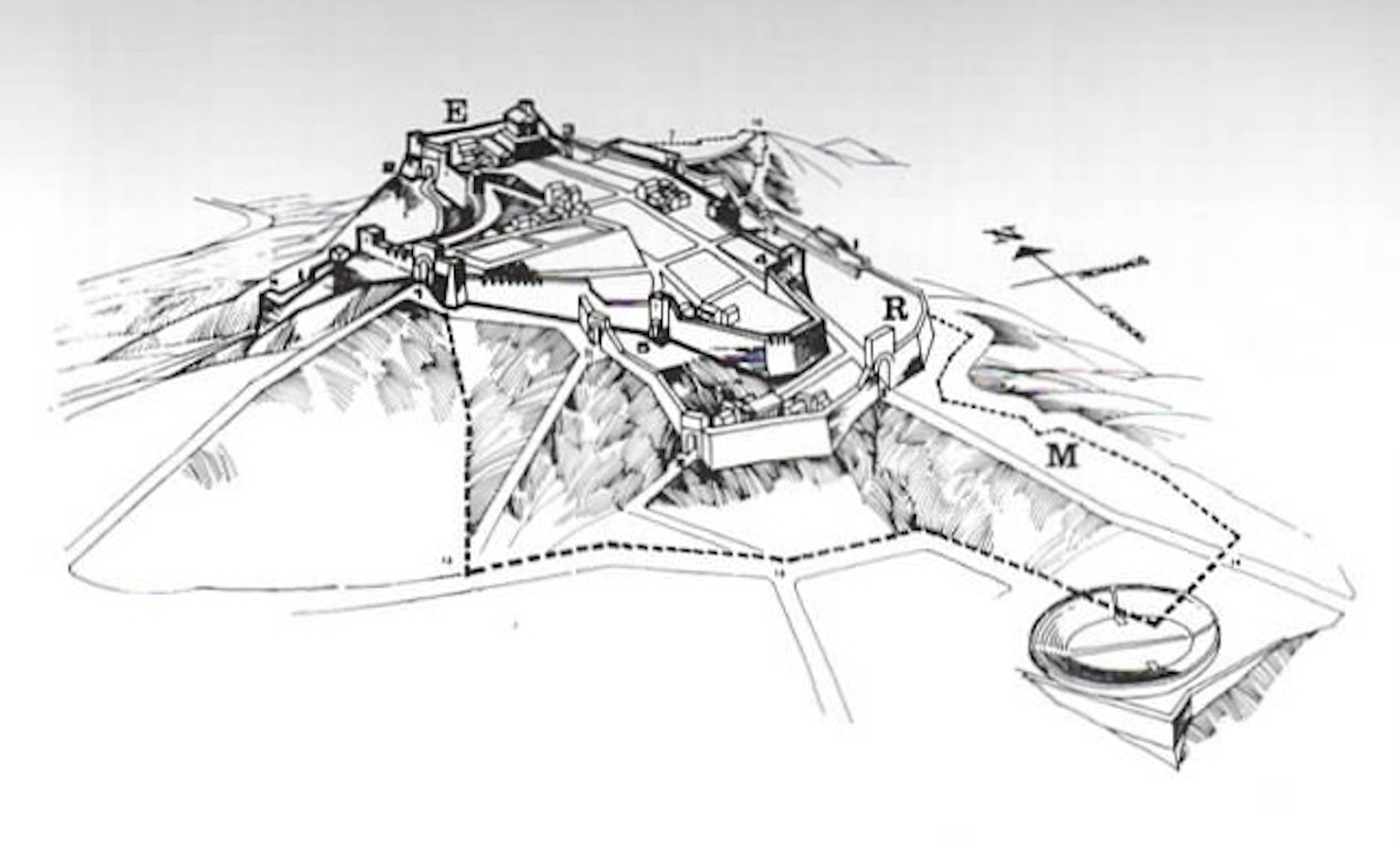

In 42 B.C., Todi became part of Italy’s 6th region in Augustus's division (including Assisi, Spello, Città di Castello, Foligno, Gubbio, Bevagna, Amelia, Narni, Spoleto, Trevi, Bettona...), adopting the name 'Colonia Julia Fida Tuder,' or 'Splendidissima Colonia Tuder,' as inscribed on a plaque in the Abbey of San Faustino. The Roman era saw the city’s expansion with structures like a theater, amphitheater, baths, several temples, the supporting wall known as 'Nicchioni,' over 30 underground water cisterns beneath the main square, a second ring of strong walls (where entrances such as Porta Catena, Porta Santa Prassede, Porta Aurea, and Porta Libera still survive).

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, Todi was looted by Goths, Byzantines, and Lombards due to its position along the Byzantine Corridor, which connected Rome to Ravenna, but largely escaped devastation. Christianity spread through Saint Terenziano, establishing both a religious (ecclesia) and territorial (civitas) presence. In 760, the Lombard King Desiderius set Todi’s boundaries, which were shaped by prominent families such as the Arnolfi, Montemarte, and Atti.

The city saw a second golden age starting in the early 1000s, becoming an autonomous commune. In 1201, the office of podestà (a mayor-like figure) was introduced, with the position of 'captain of the people' (a judge-like figure) following in 1250. Interestingly, the podestà could not be from Todi to avoid local bias or 'influences.' The commune boasted a formidable cavalry, enabling Todi to expand southward, conquering Montemarte castle and allying with powerful Perugia. This period saw the construction of a third circle of walls with gates such as Porta Romana, Porta Perugina, Porta Orvietana, and Amerina, alongside grand political and religious buildings like the Cathedral of the Annunciation (Duomo), the Palazzo del Popolo, Palazzo del Capitano, Palazzo dei Priori, the aqueduct, and the Scannabecco fountain.

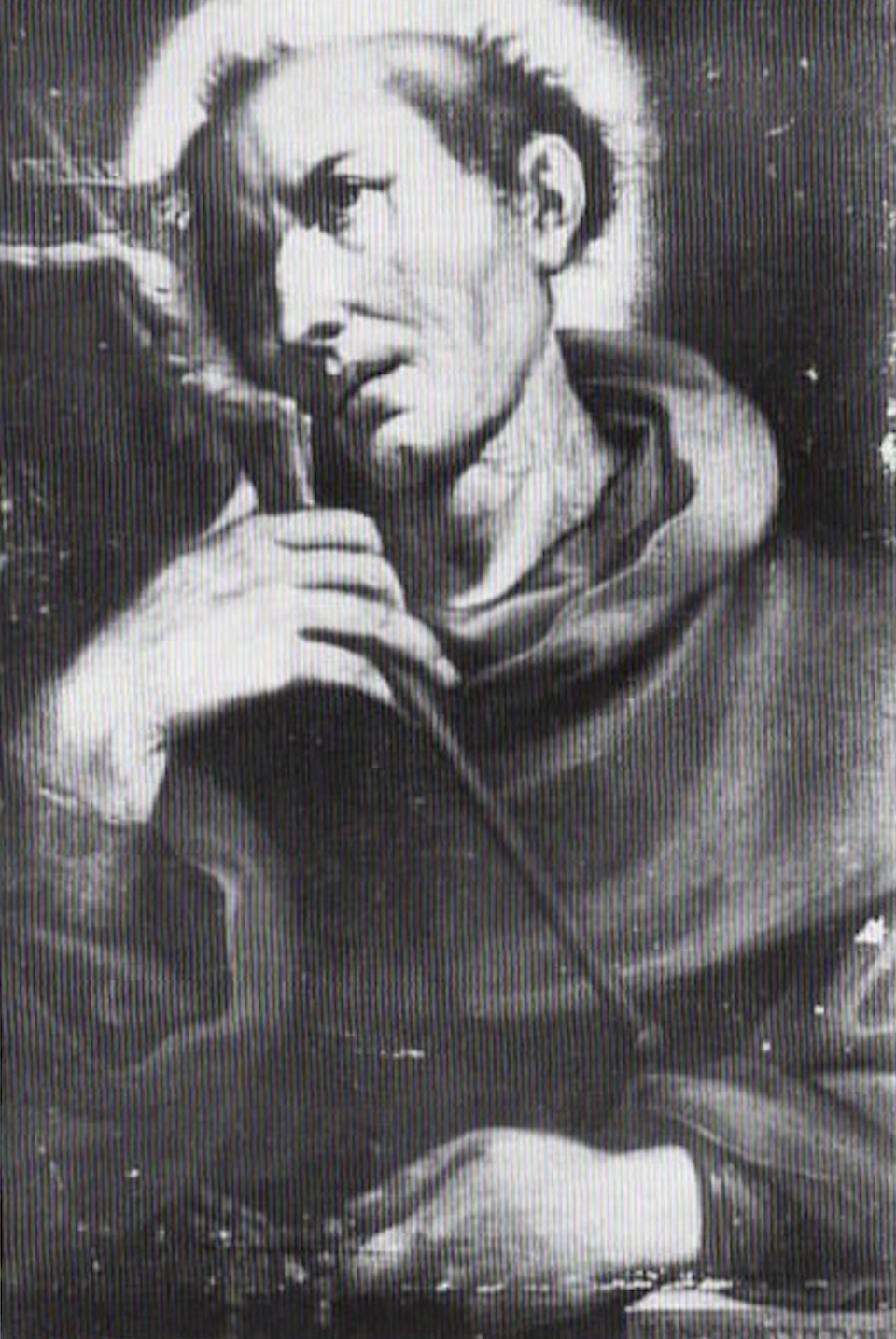

During the fierce struggles between the Empire and the Papacy emerged Jacopo de Benedetti, known as Jacopone da Todi. This lay friar opposed Boniface VIII, whom he blamed for the Church's spiritual decline, and his poetry is one of the earliest examples of the Italian vernacular.

In 1367, Todi lost its autonomy and came under Church jurisdiction amid bloody feuds between Guelphs and Ghibellines and changing rule by noble families such as the Malatesta of Rimini, Biordo Michelotti, Ladislaus of Anjou, and the Perugian noble Braccio Fortebraccio da Montone. The plague that devastated Italy also affected Todi, temporarily halting its decline with the completion of the Temple of San Fortunato.

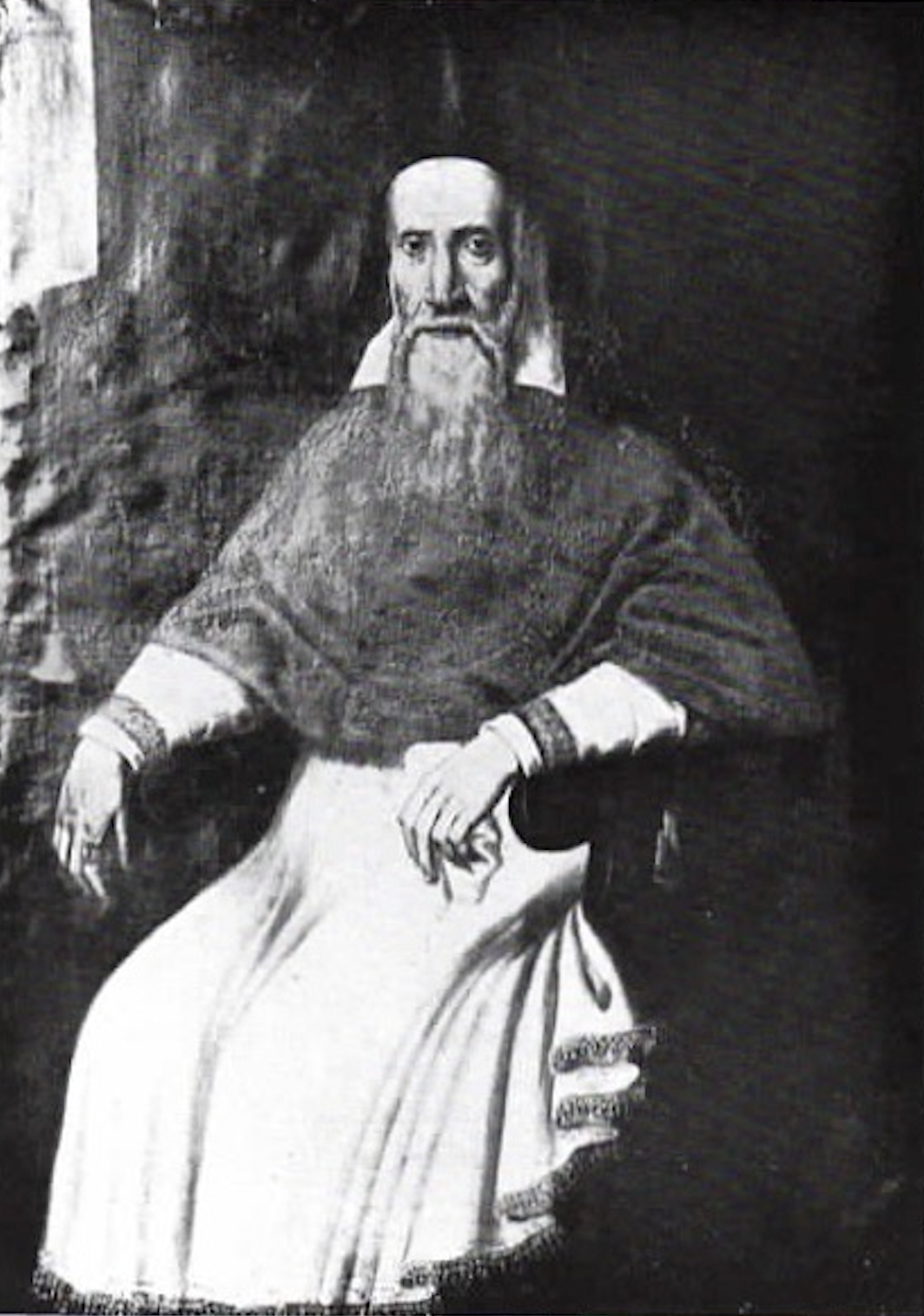

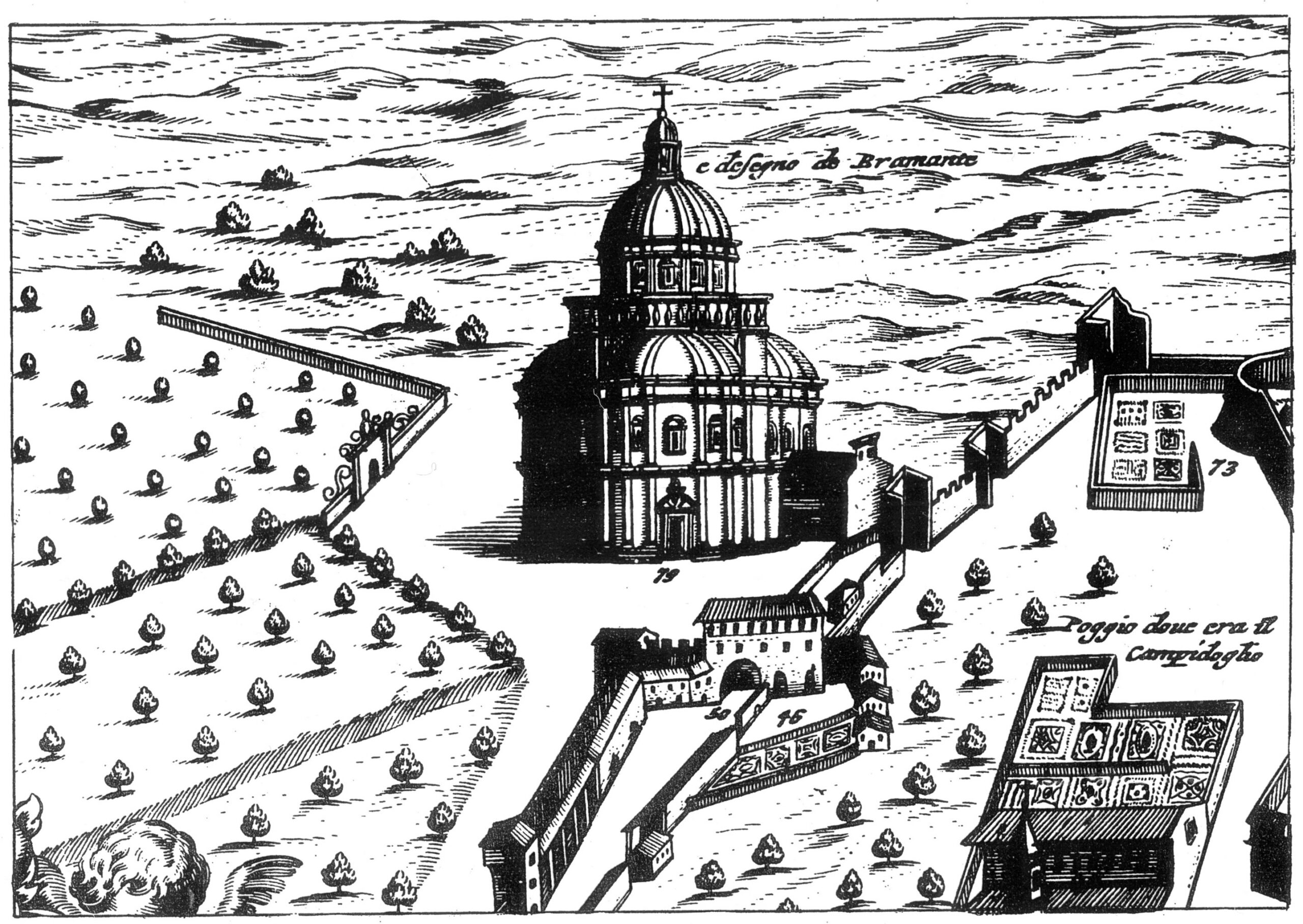

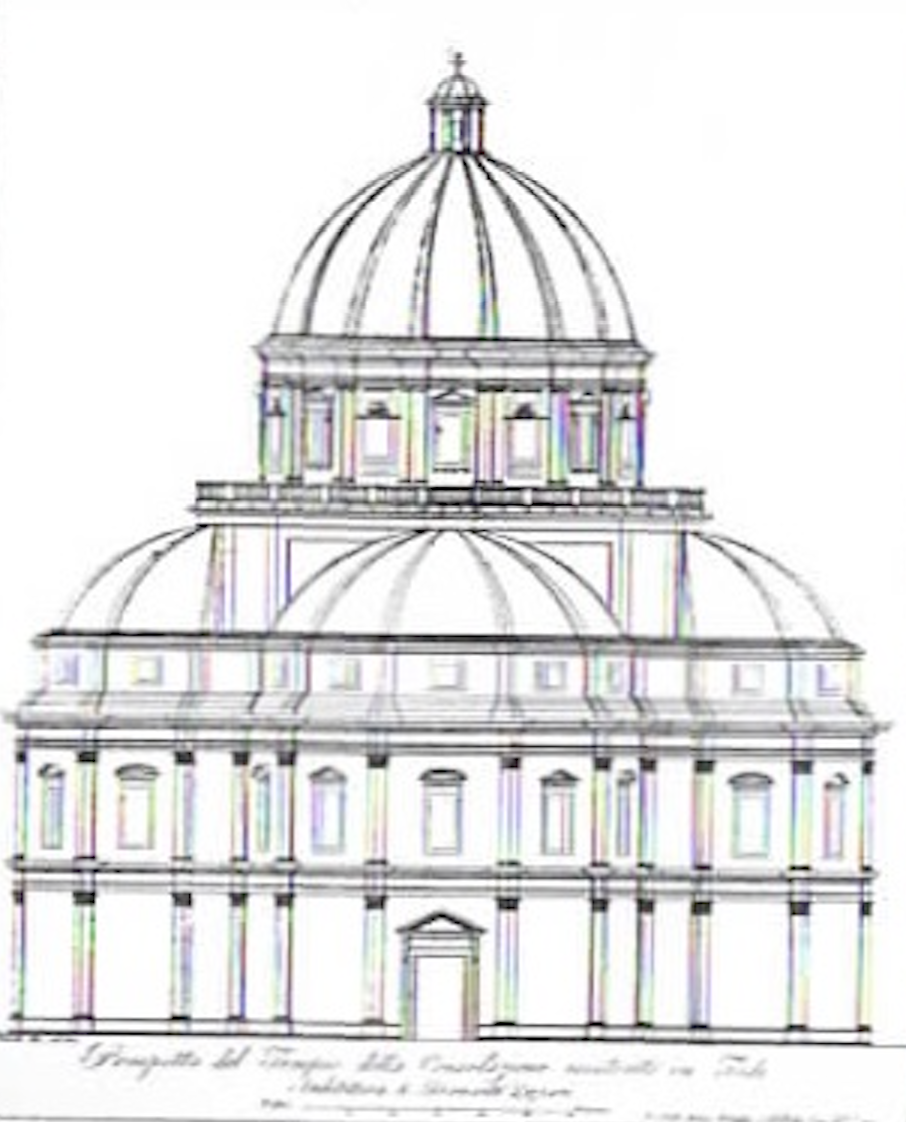

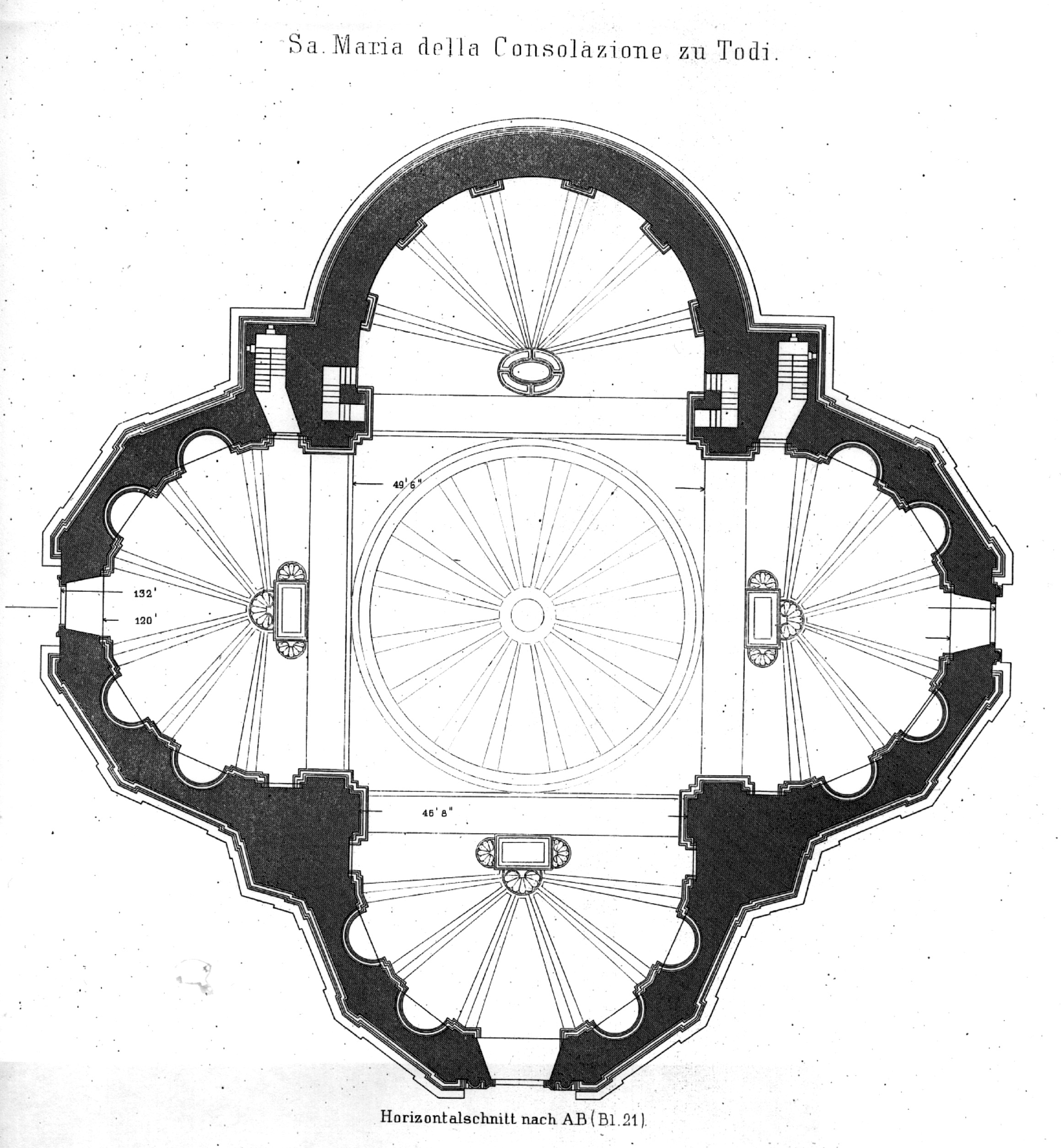

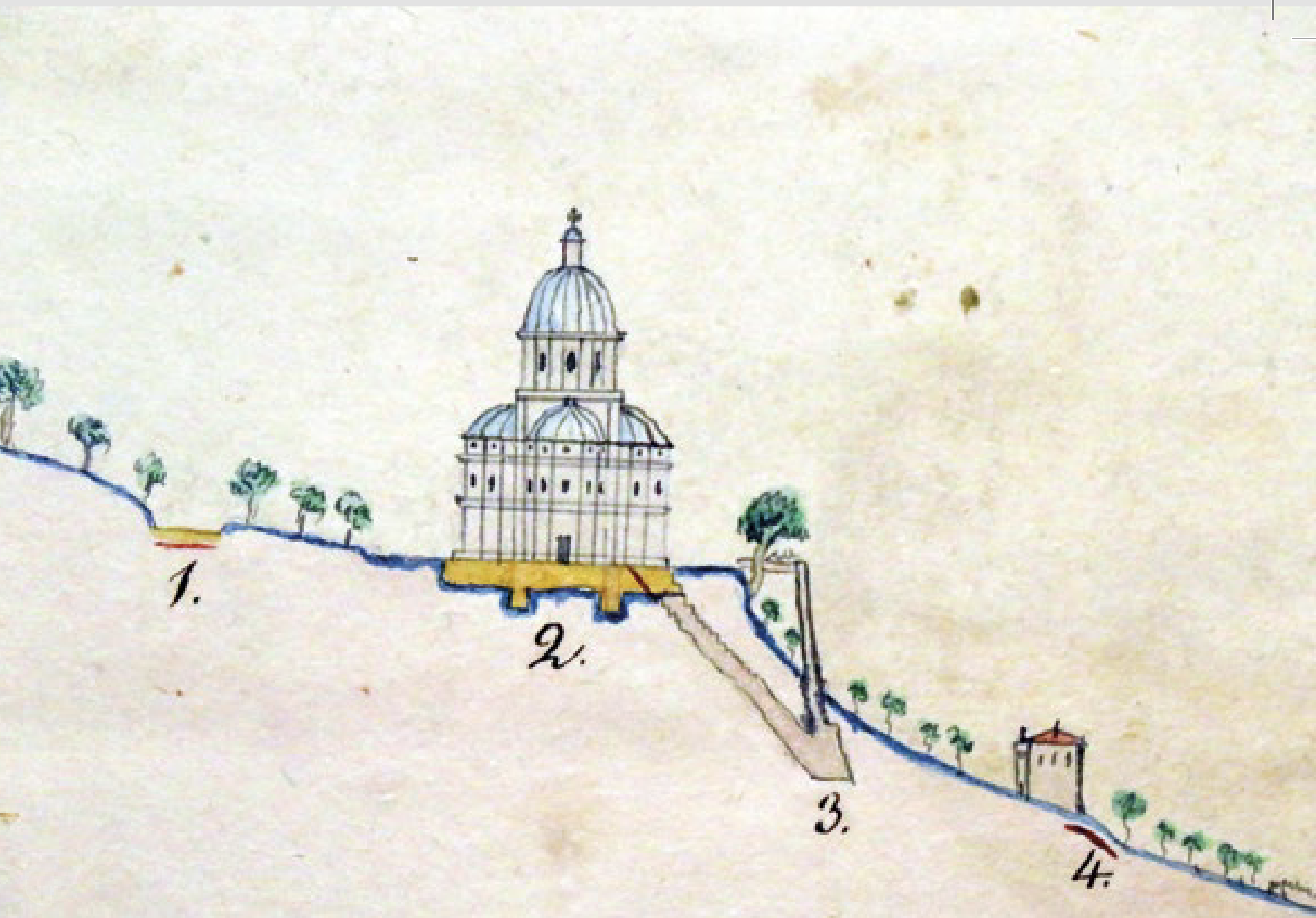

The latter half of the 1500s was marked by the dominance of the Cesi family, who provided four bishops, the last of whom, Angelo (1566–1606), led the city into the Counter-Reformation. Angelo Cesi’s grand vision brought Todi extensive urban, cultural, and artistic renewal, with major works such as the Church of Santa Maria della Consolazione, attributed to Bramante and completed in 1607, the Episcopal Palace, the Church of the Holy Cross, Cesia Fountain, Nunziatina Church, Viviano degli Atti Palace, and restorations of the Cathedral, where he painted the Last Judgment on the counter-facade, and Cesia Street.

The 17th century was a challenging time for Todi, marked by famine, war, and epidemics. The devastating plague of 1630 prompted the people of Todi to create a large wooden statue of Saint Martin, kept in Santa Maria della Consolazione as a votive offering. These years saw a population decline, with nobles retreating to country estates and convents filling up.

Todi remained under Church rule until 1860, when it became part of the Kingdom of Italy. The people of Todi played an active role in Italy’s Unification, participating in the Independence wars and the Expedition of the Thousand, fighting and dying for freedom and unity. When Garibaldi crossed Italy, staying at the Cappuccini convent, the people of Todi planted a cypress tree in memory of the event, still visible in a garden below Piazza Garibaldi, where his statue stands.

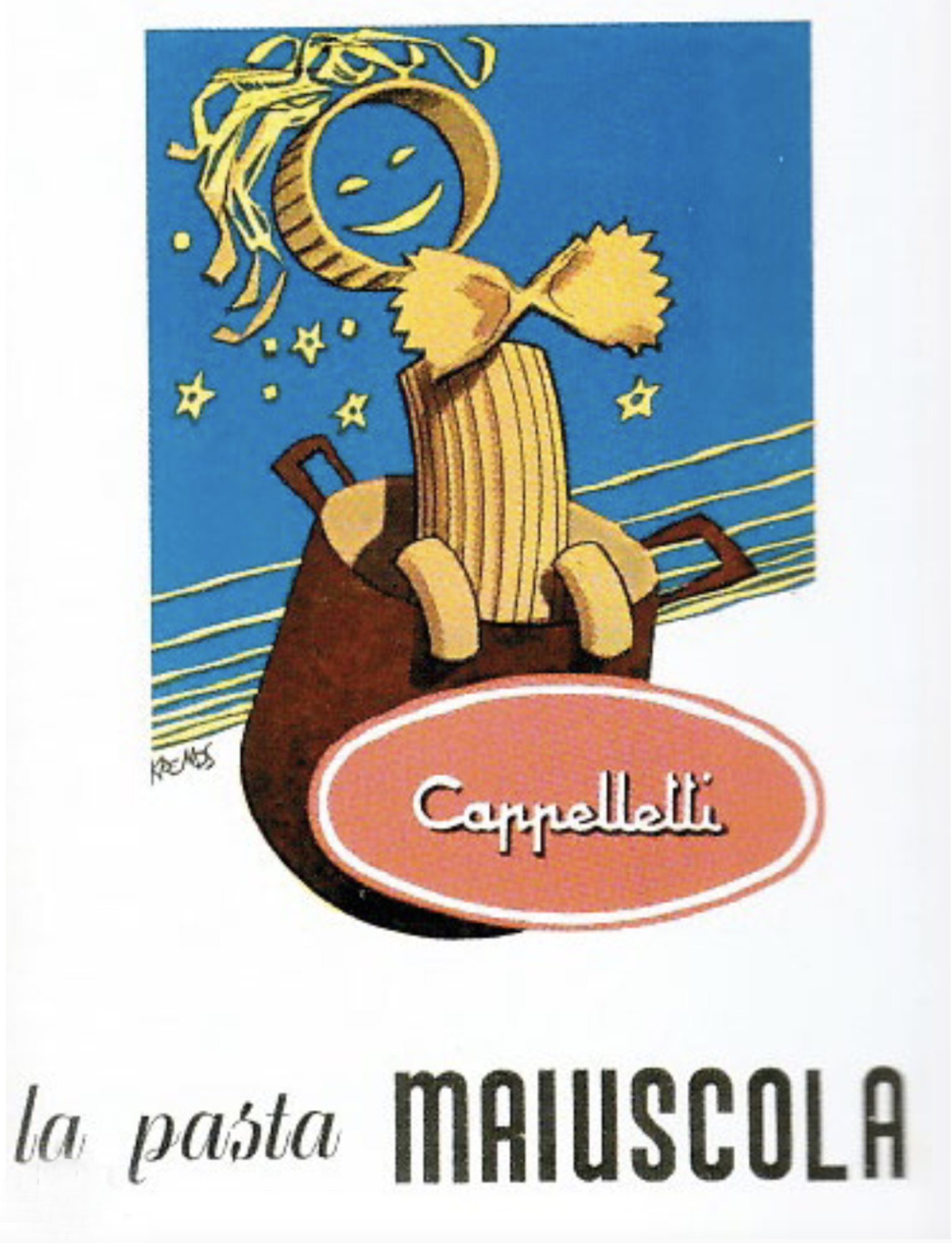

The 20th century found Todi and much of Umbria in a state of political and economic backwardness, with inadequate industrialization and poor infrastructure. The situation improved thanks to Augusto Ciuffelli, who, as Minister of Public Works (1914–1915), implemented a new aqueduct, the construction of the Central Umbrian Railway, and enhancements to the Agricultural Institute now named after him. Important local industries like 'Carbonari' (agricultural machinery), 'Toppetti' brickworks, and 'Cappelletti' pasta mill emerged. Educational institutions like the 'Jacopone da Todi' Gymnasium-Lyceum and a boys' orphanage founded by Luigi Crispolti produced skilled artisans, especially carpenters and printers. The Francischi Palace is now a renowned center for eating disorder treatments in Italy.

The economy, historically based on agriculture and livestock, has seen little industrial transformation, preserving the landscape.

In 1982, Todi made tragic news due to a fire at Palazzo del Vignola, where 35 people lost their lives.

The town experienced significant depopulation following the end of sharecropping and the agricultural crisis, but in the last 20 years, Todi has achieved renown for its exceptional quality of life, overcoming its isolation to become a strong cultural and tourist hub.

.

- Il volo dell’aquila

- Gola del Forello

- Marte di Todi

- Elmo attico dal corredo della tomba rinvenuta nel 1915

- La leggenda di fondazione, Ignazio Mei 1719

- Il colle su cui si sovrapposero le città etrusca, romana, medievale

- Stemma di Todi, 1340

- Il vescovo Angelo Cesi

- Papa Bonifacio VIII

- Jacopone da Todi, tela di Ferrau da Faenza XVII sec.

- Borgo Nuovo, 1630

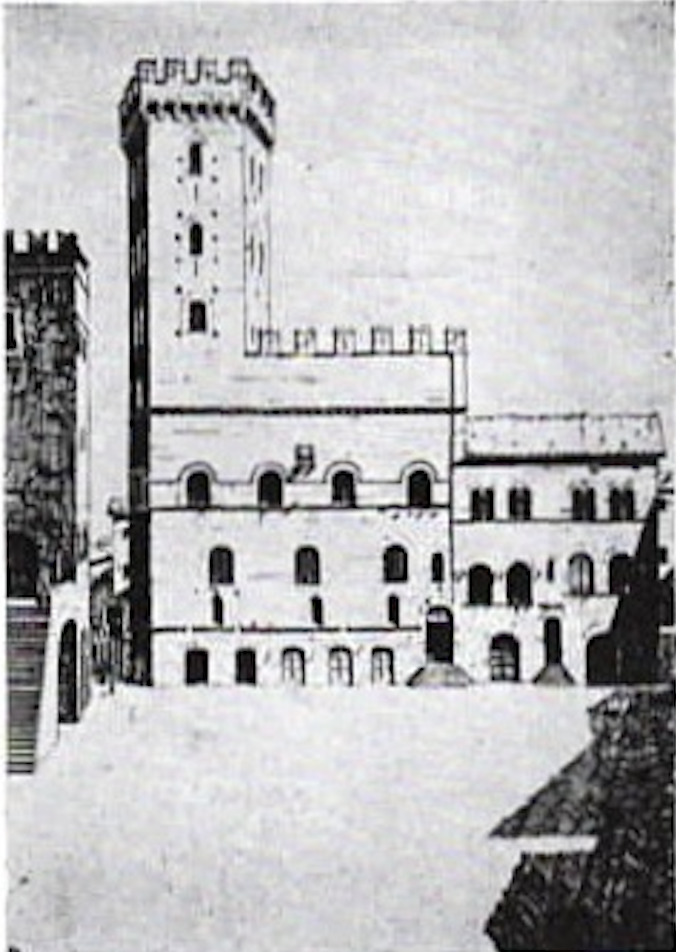

- Palazzo dei Priori prima del restauro voluto da papa Leone X

- L’imperatore Traiano in visita a Todi, Polinori 1629

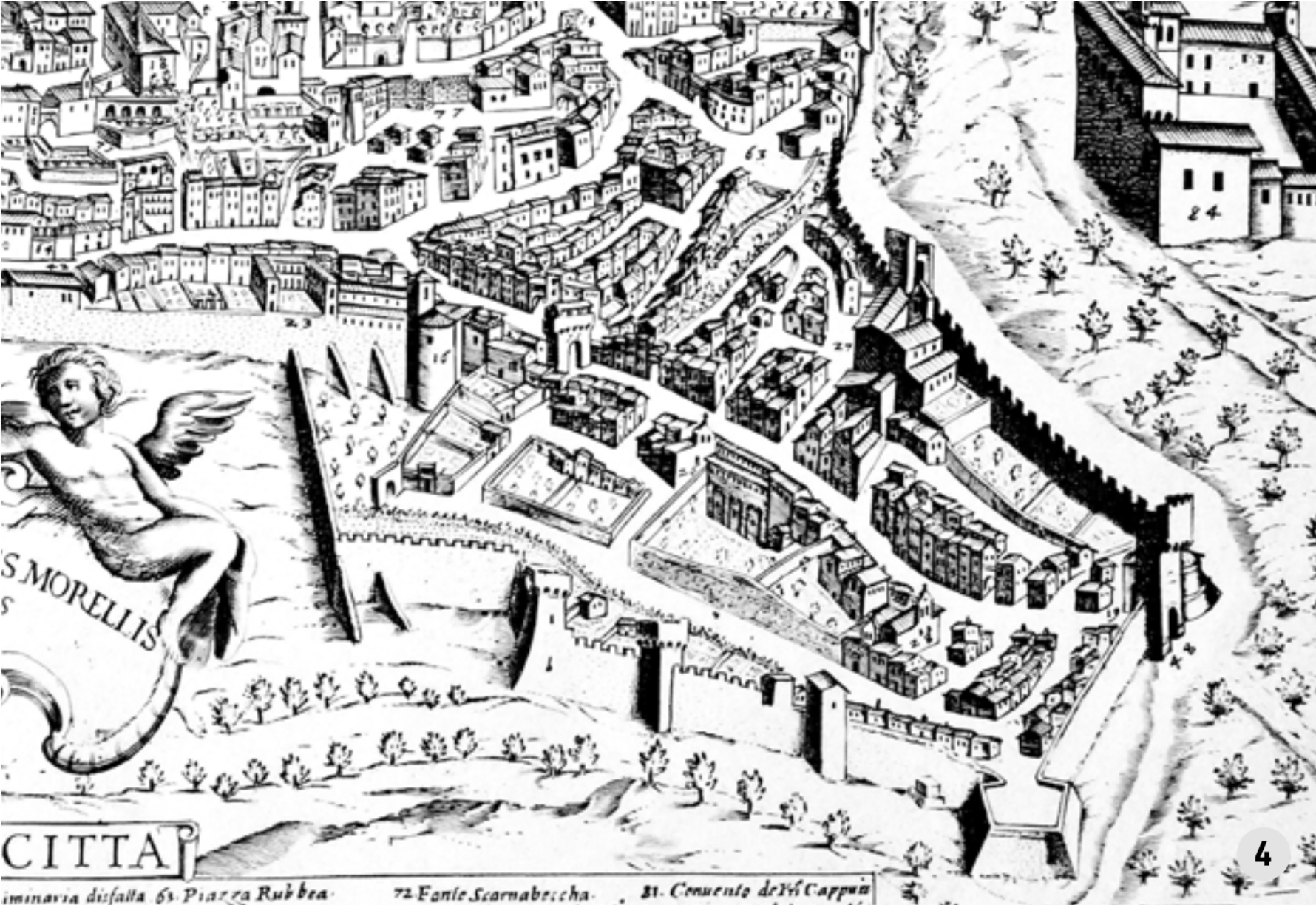

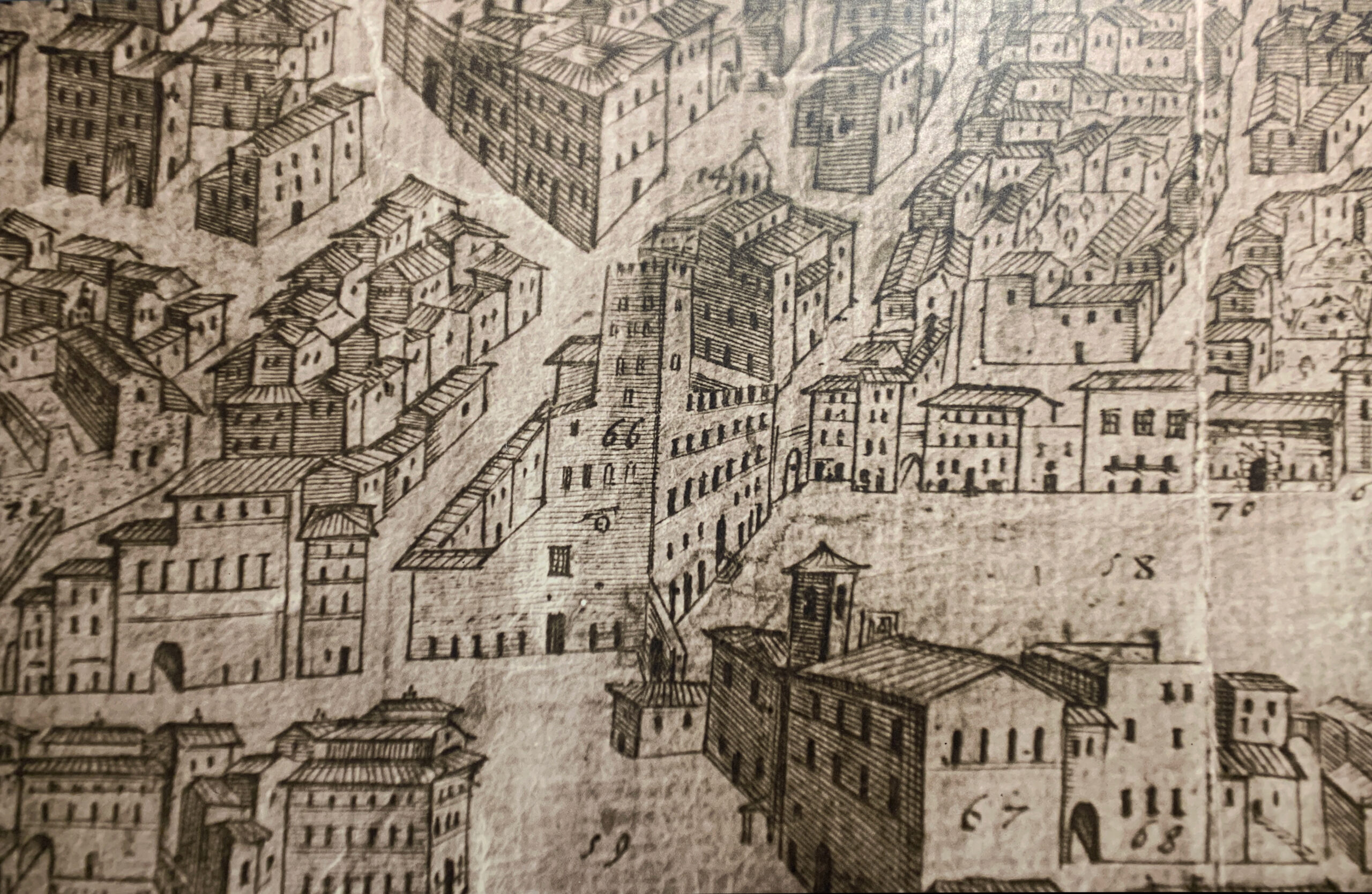

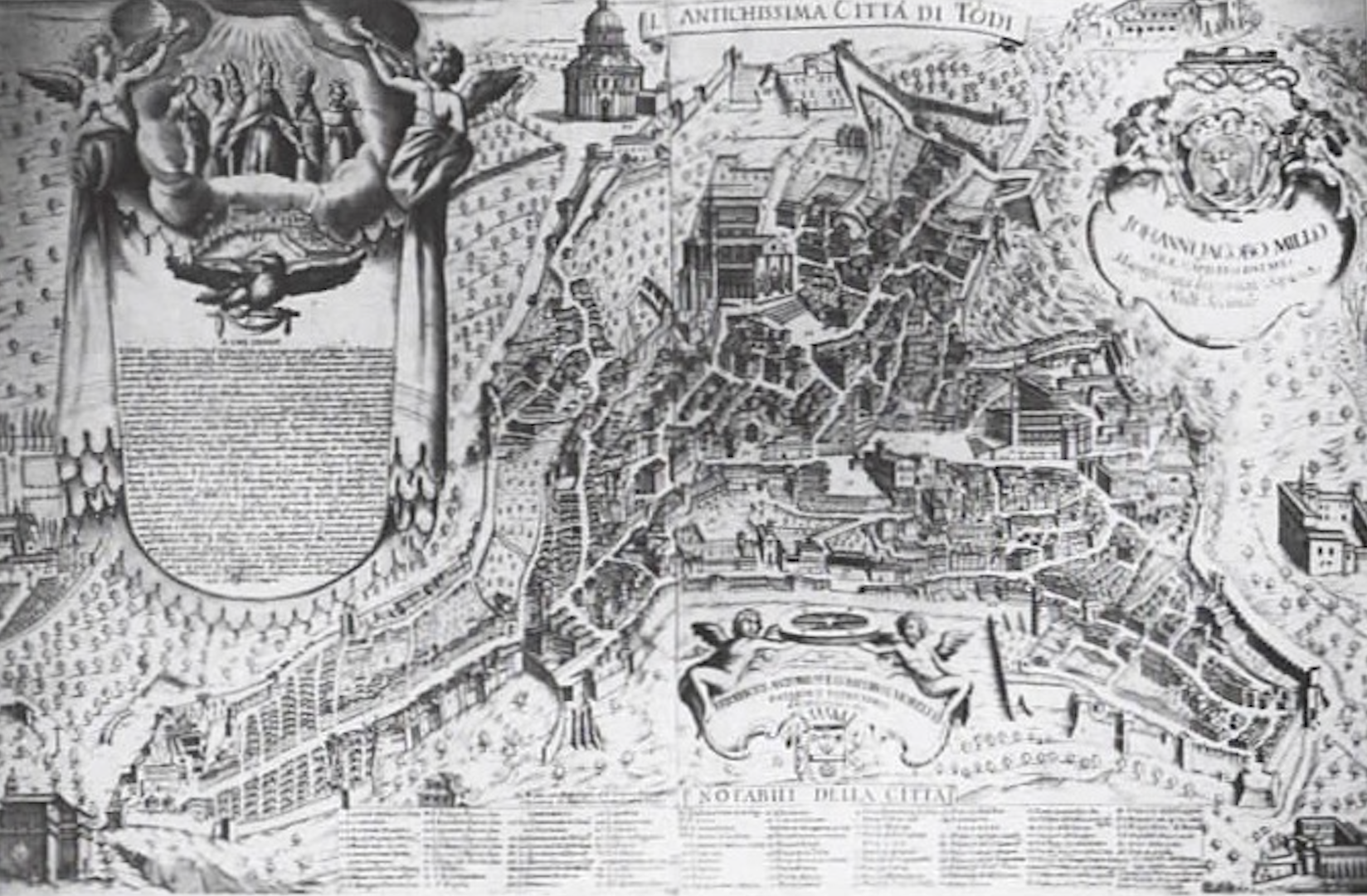

- Pianta di Todi, 1633

- Acquaforte dell’800 del Tempio della Consolazione

- Progetto del muro di Luigi Poletti, Tempio Consolazione

- Profilo Tempio Consolazione, dilamazioni dalla Rocca alla confluenza con il Naia, XIX sec.

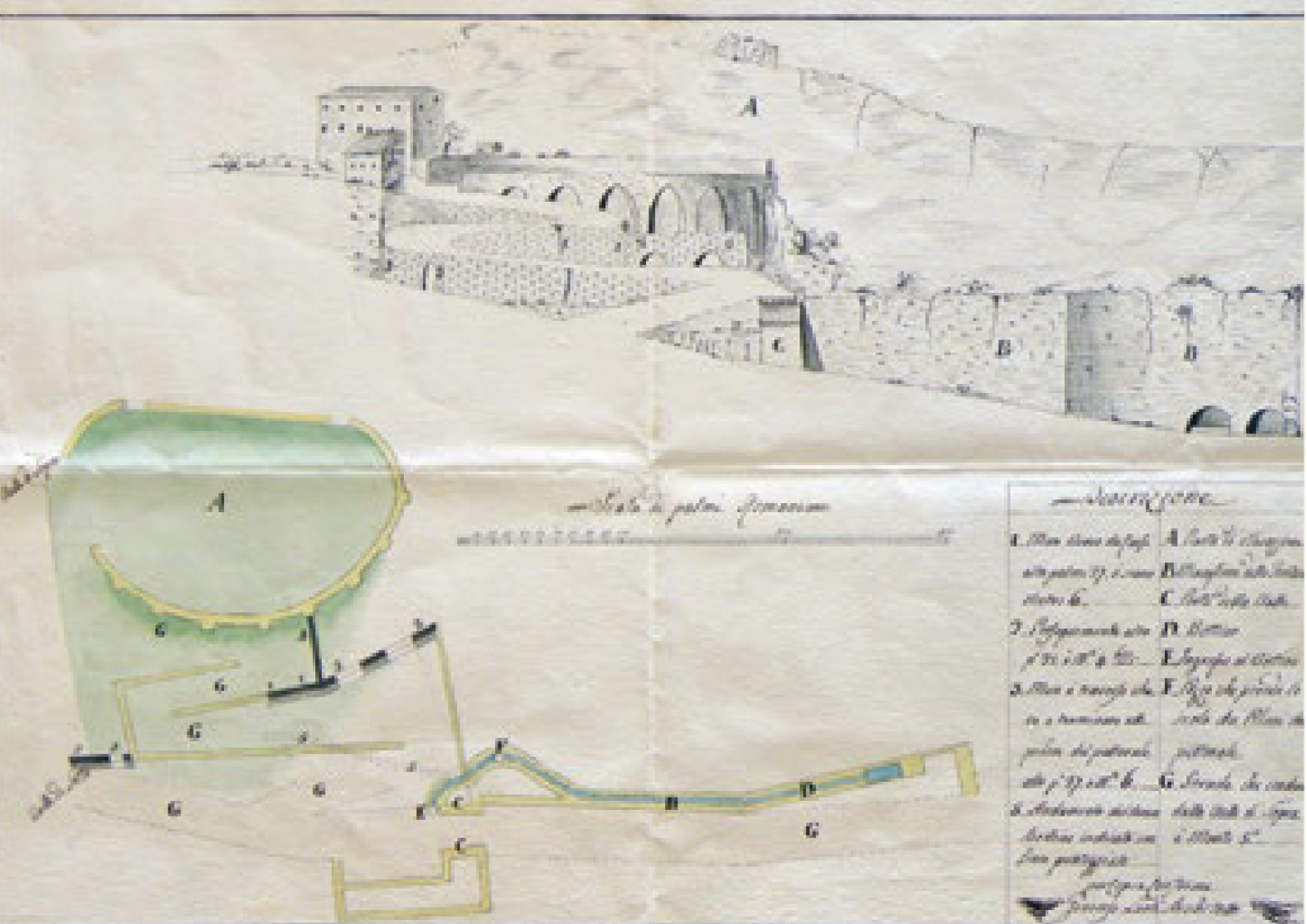

- Porta della valle e muri di contenimento. 1811

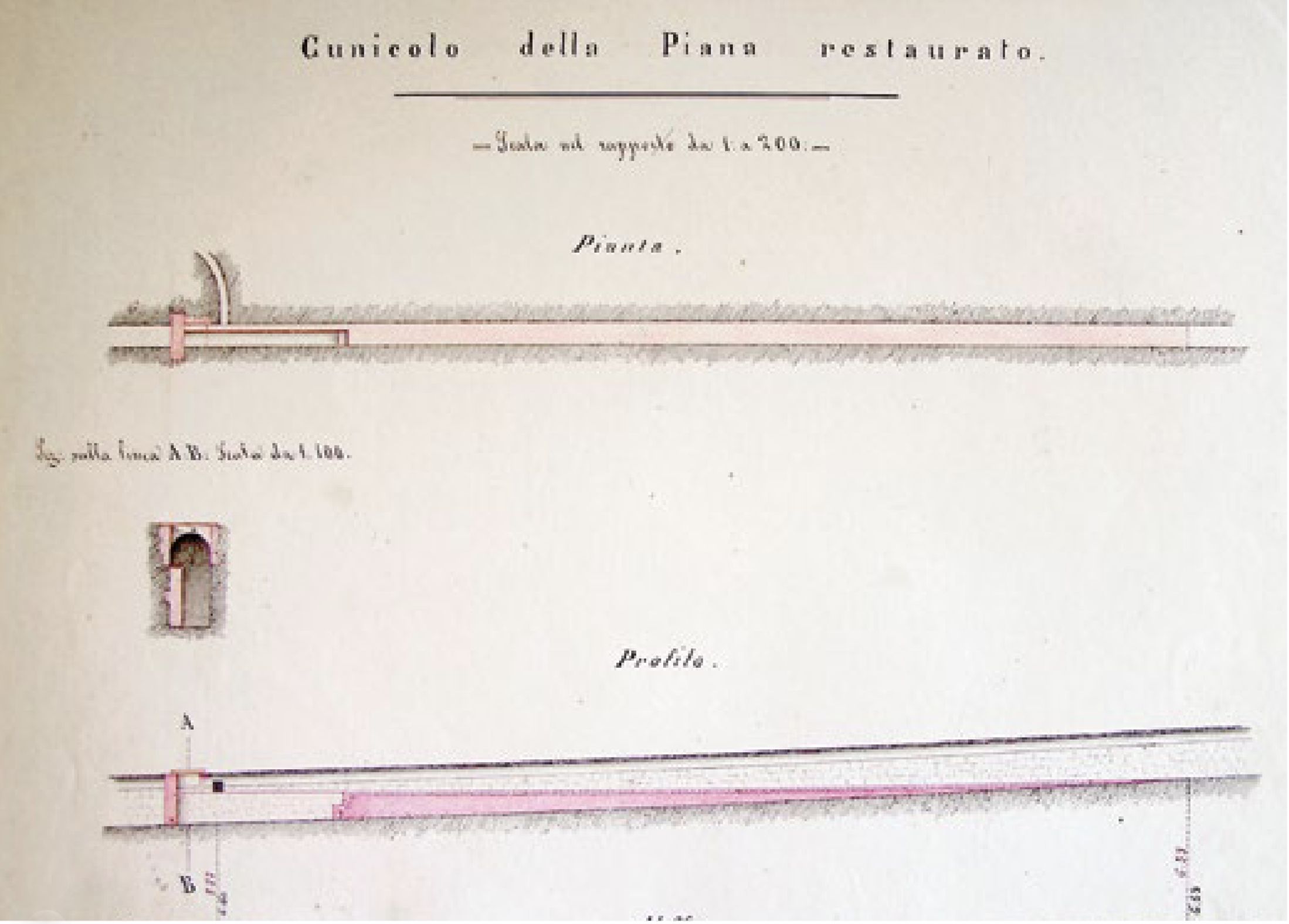

- Modifica al cunicolo della Piana per la costruenda fontana del Bottini, 1872

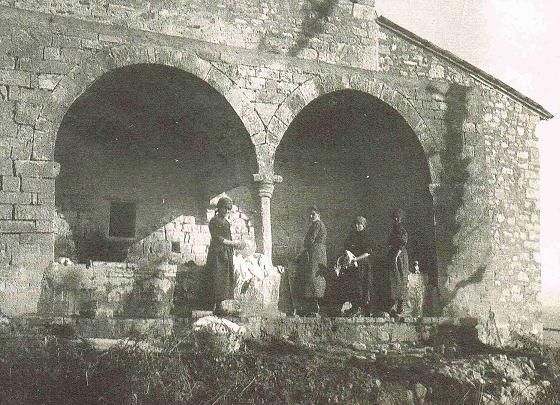

- Todi, Ospedale della Carità 1794

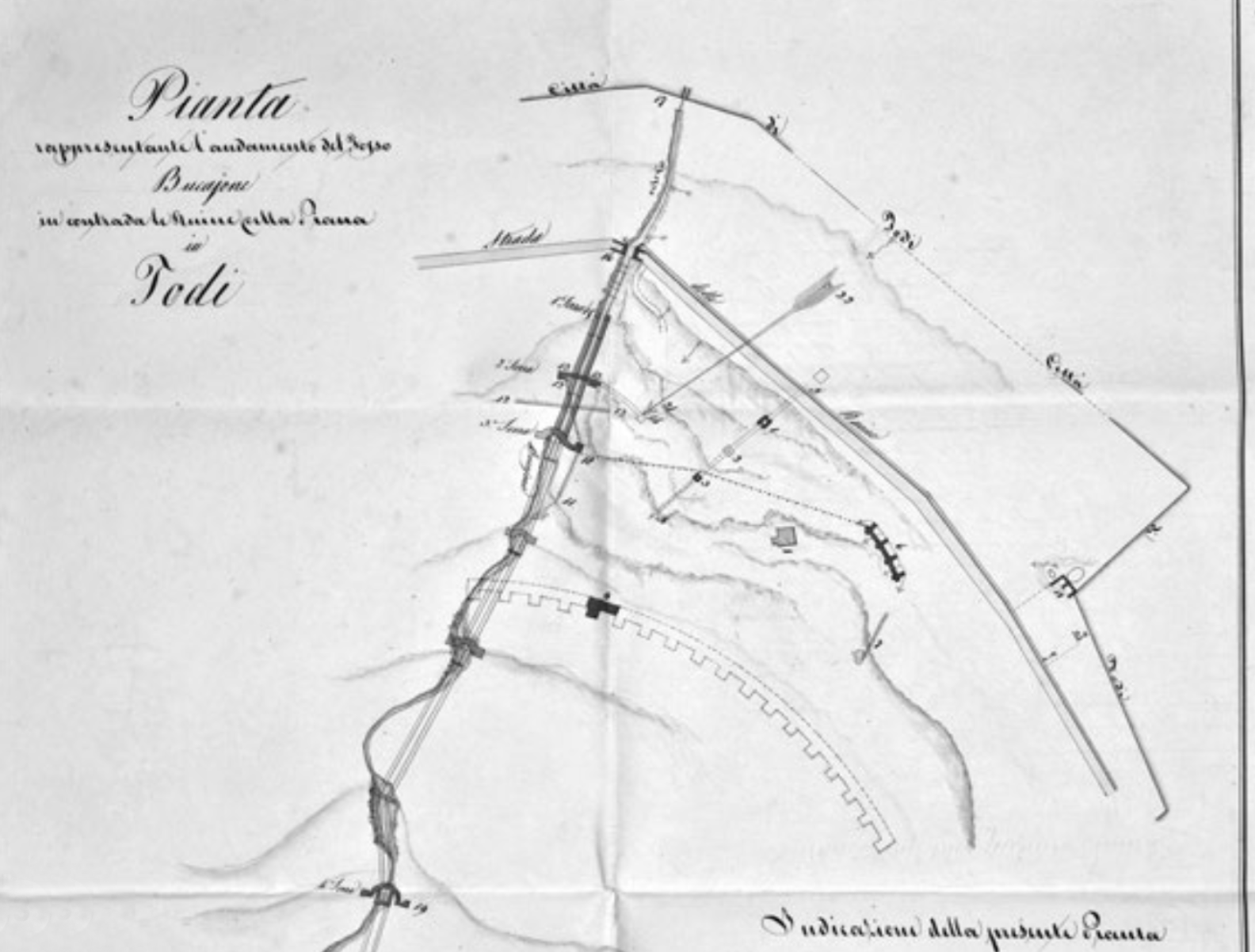

- Pianta della Piana con Muro Vici da completare. 1844

- Pianta di Todi, XVII sec.

- Donne alle Fontanelle di Sant’Arcangelo, 1890

- Nuova strada di Porta Romana, inizi XX sec.

- Diploma massonico rilasciato da Girolamo Dominici a Luigi Berti

- Milite della guardia civica, 1860

- Todi con il “muro etrusco” e la “valle inferiore”, 1913

- Via Borgo Nuovo, Marchi 1927

- Il Duomo. Da notare il campanile originario con cuspide a piramide

- Piazza del Popolo ed il Duomo. Foto storica

- Piazza del Popolo. Foto storica

- Todi con Porta Romana, 1913

- Sonetto a Todi di Gabriele D’Annunzio

- Porta Perugina, 1920

- Todi, 1930

- Via Borgo Nuovo. Foto storica

- Pianta di Todi con tracciato delle mura medievali

- Todi, 1930

- Veduta del Tempio della Consolazione, foto storica

- Todi, 1973

- Todi, 1978

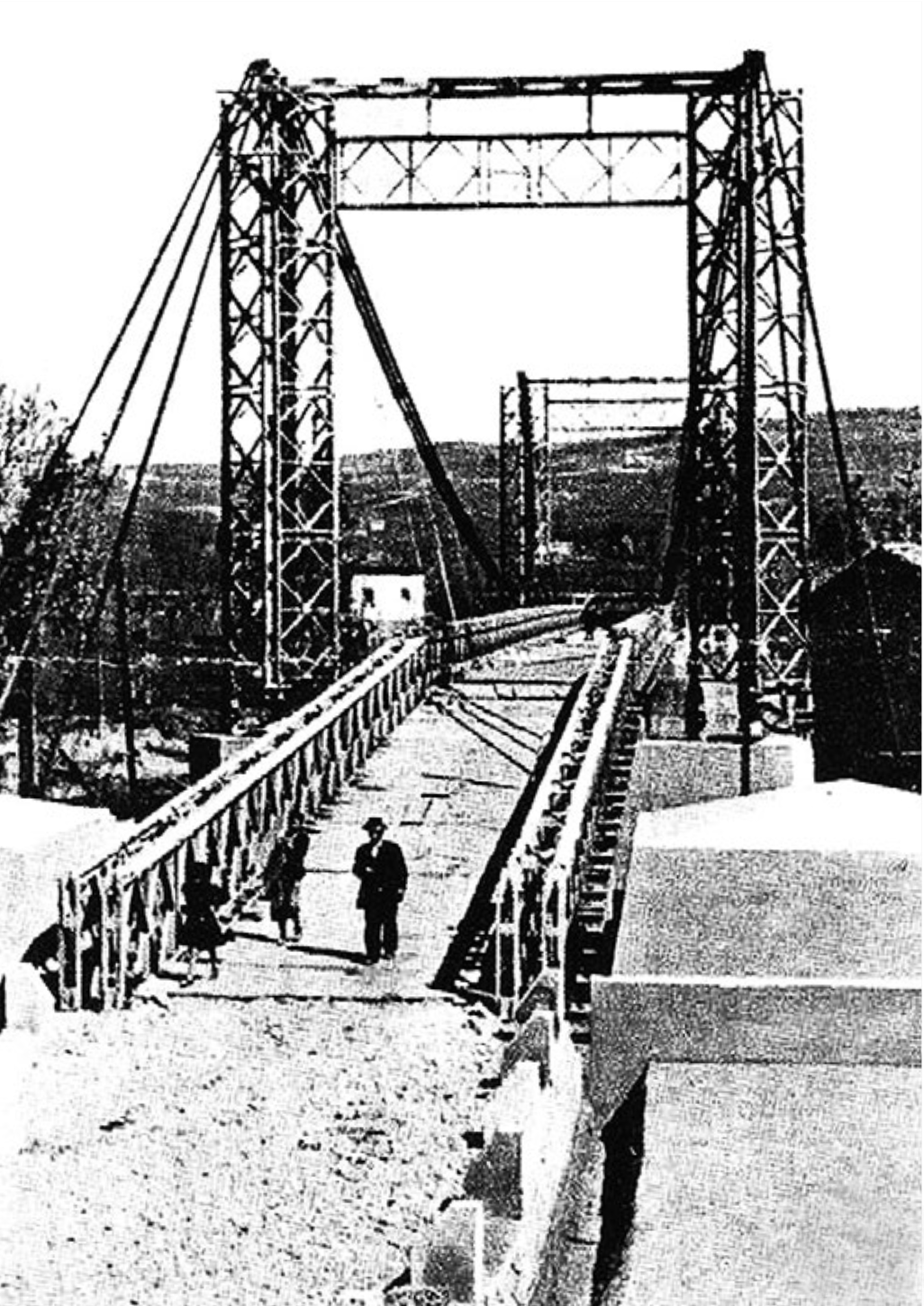

- Ponte di ferro, foto storica

- Il Ponte sospeso di Pian di San Martino, inaugurazione 1953

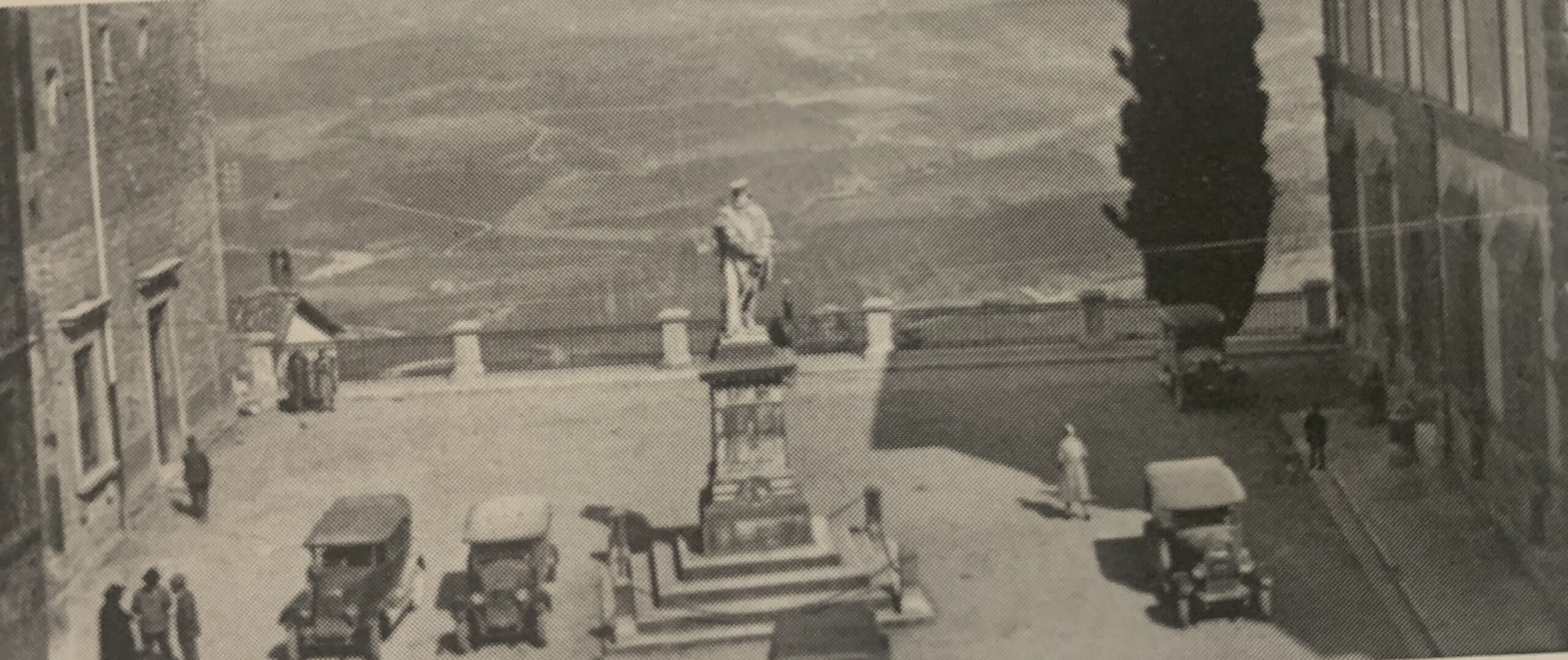

- Piazza Garibaldi, 1930

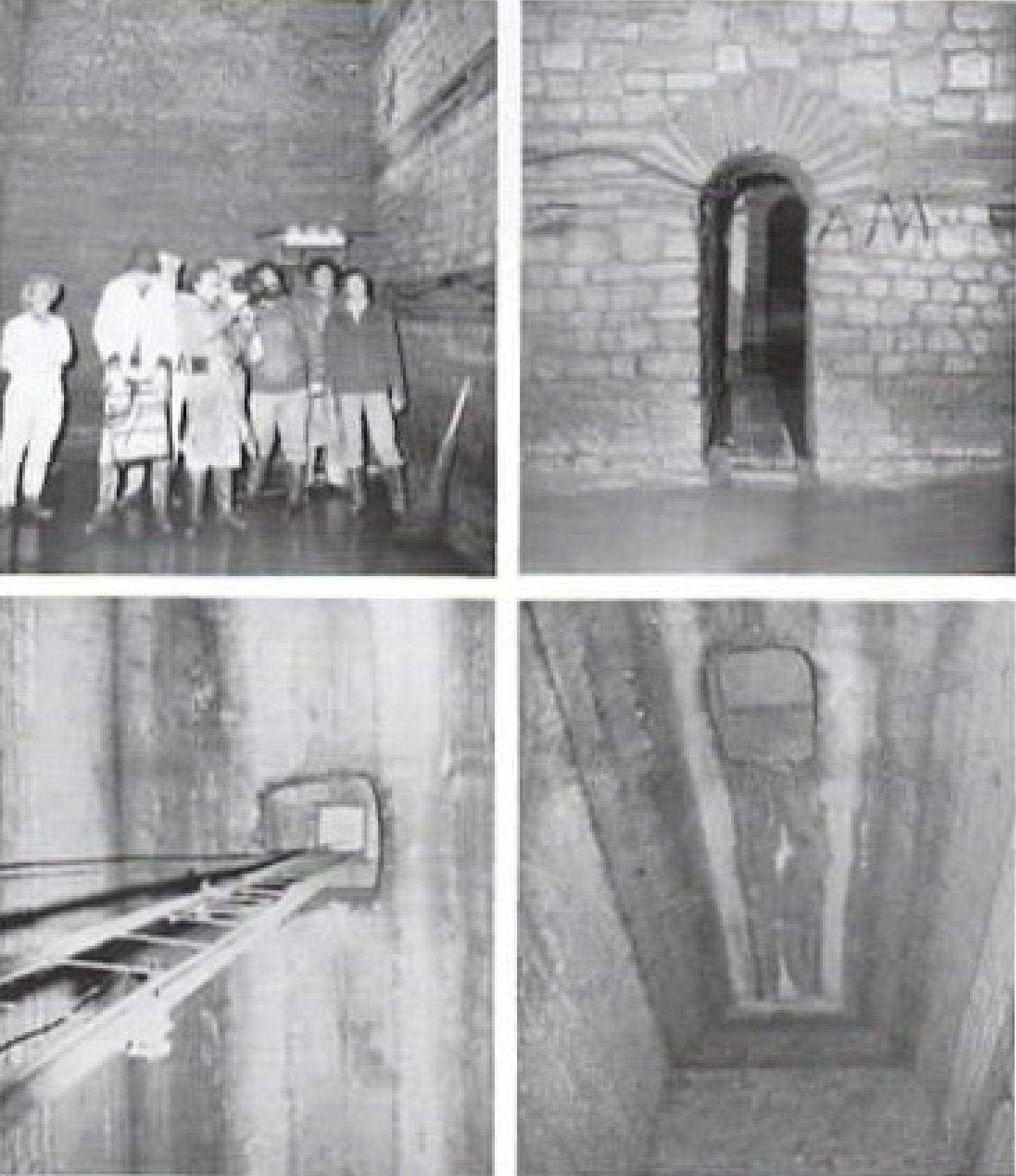

- Originaria pavimentazione romana, 1963

- Le cisterne romane di piazza

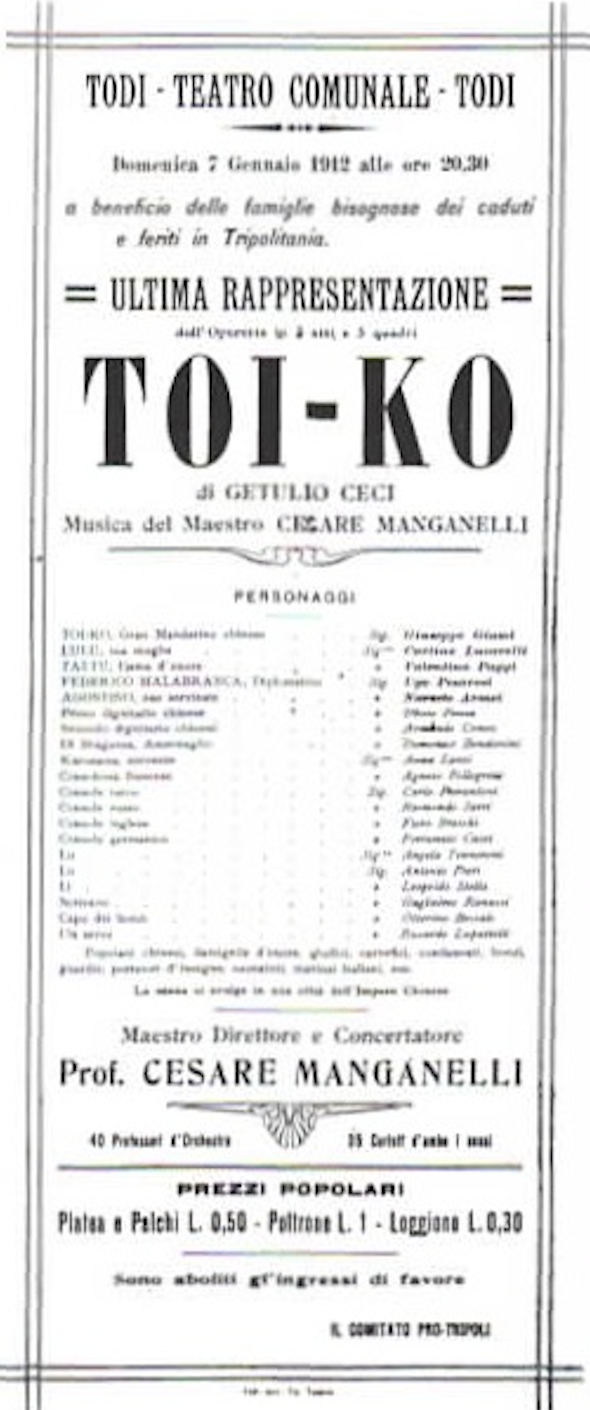

- Locandina Teatro Comunale, 1912

- Pastificio Cappelletti

- Il molino e pastificio Cappelletti distrutto dai tedeschi, 1944

- Galleria ferroviaria in costruzione, inizio XX sec.

- Confezione della pasta Cappelletti

- Famiglia di contadini a tavola, 1928

- Barbieria tra le più antiche d’Italia, 1869

- La Barbieria tra le più antiche d’Italia, oggi